What is a geode?

Geodes are nodules lined with quartz. They are found in sedimentary and igneous environments. In the eastern United States, geodes are found in sedimentary rock layers, including limestone, siltstone, and shale.

The smallest are pea-sized. The largest can exceed three feet (one meter), although these are very rare and often discolored by or filled with clay, making them unattractive.

Geodes may be solid when the quartz crystals have grown to fill the interior. The favorites are those with secondary minerals (describe below). In some locations, geodes may be 90% solid or have only small pockets of crystals. These are hard to crack open.

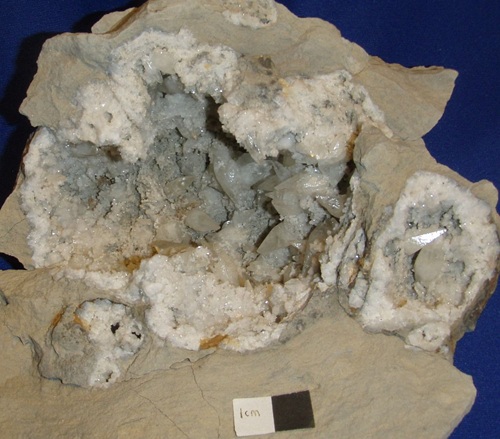

The exterior shell of a geode is formed from cryptocrystalline quartz, commonly called chalcedony (Kal-se-doh-nee). Sometimes, chalcedony dominates the interior, forming bubble-like masses. In its pure form, chalcedony is white to pale blue, but it may be colored by groundwater to other colors.

Agates are geodes that are often filled with chalcedony, having multiple colors. The highly sought-after Kentucky Agates have a spectrum of colors, including black, white, red, yellow, blue, and shades thereof. Some are banded, a pattern called “fortification.” (Like the walls of early forts.) These agates are found on private property in Rockcastle and Estill Counties, Kentucky.

“Geodes belts” define occurrences that follow specific rock layers along linear outcrops. For example, in Kentucky, the geode belt runs from Meade, Bullitt, and Hardin Counties south and east, until the rock strata run under the Cumberland Plateau. Outcrops occur south into Tennessee.

Indiana’s geode belt is ill-defined north of the Ohio River, and appears in Washington, Lawrence, Brown, and Monroe Counties before disappearing under glacial till.

How do geodes form?

The most recent theory in the Ohio Valley, geodes begin as gypsum nodules (calcium sulfate) in Mississippian-age sedimentary rocks in the Ohio Valley. Gypsum is water-soluble and migrates through rocks that are buried deep within the Earth. The thickest gypsum beds are in the St. Louis Limestone. Groundwater carries the dissolved gypsum, mostly into old rock layers, where the gypsum precipitates into nodules inside fossils or other features with space for molecules to congregate and expand.

Later, groundwater deposits a rind of chalcedony around the nodule. These so-called proto-geodes are gypsum nodules with a thin exterior, sometimes barely visible. Over time, the rind thickens. Some geodes have microscopic gypsum preserved in the quartz rind.

After that, anything goes. Gypsum usually dissolves away, leaving a hollow interior that has additional quartz added. When the quartz doesn’t fill the interior, groundwater can bring in other elements. Sulfur combines with barium or strontium to form barite and celestine, respectively. Iron can form pyrite or marcasite.

Unusual minerals occur in geodes where the bedrock forms structures, like the Cincinnati Arch or the Muldraugh Dome. These subsurface “topographic” highs can concentrate elements that would otherwise be too dispersed to form crystals. Halls Gap contains abundant nickel (probably from iron-nickel meteorites that rain down on Earth continuously over millions of years) to form millerite. It also has copper, lead, and titanium. Muldraugh/Fort Knox has celestine, fluorite, petroleum, strontianite, and sulfur.

How do I open a geode?

The safest way is to use a rock splitter. However, those are expensive and only cost-effective if you plan to open (and sell) a LOT of geodes. Using a hammer and chisel is the most common approach. However, it is dangerous. Flakes or chunks of quartz are just like glass. They fly off at high velocities and can easily penetrate skin and eyes!

Solid geodes can go sailing away like a golf ball hit by a club. Contain the space when attempting to open a geode. That will minimize the risk of denting a car, breaking a window, or hurting someone watching. (Observers should wear goggles and be dressed for safety.)

Wear safety gear when opening geodes. That includes safety goggles, a long-sleeve shirt, and heavy pants, such as blue jeans.

Some people put the geode in an old sock before they crack it open. It doesn’t take long to wear out the sock. Others wedge the geode with the tip of their boot. Steel-toed boots are best, but heavy rubber tips work – as long as your aim is accurate. Don’t do this unless you are experienced with a hammer and chisel.

Quartz has a hardness of seven on the Mohs Scale. That means the sharp edge of a chisel won’t last long. Access to a grinding wheel is essential to keep the chisel point sharp. Dull chisels are dangerous. Metal can flake off and cause as much bodily harm as a geode fragment.

Quartz Photos

Milky Quartz in large crystals. The white color is due to microscopic inclusions of water and/or gas bubbles, like CO2. The 6 cm wide geode is from Monroe Co., Indiana. Bob Harman specimen and photo.

Secondary Minerals

Secondary minerals form after the quartz. Calcite is, by far, the most common secondary mineral. Calcium carbonate makes up limestone, and when dissolved by groundwater, can crystallize in hollow geodes. This is why hard water can damage pipes and water heaters from the inside. Calcite can fill a geode, hiding other secondary minerals. Hydrochloric acid will dissolve the calcite, exposing non-soluble minerals. Examples are noted below.

Barite – Barium Sulfate – BaSO4

Barite with zoning, possibly from sulfide inclusions (pyrite or marcasite). Monroe Co., Indiana. Bob Harman specimen and photo.

Calcite – Calcium Carbonate – CaCO3

Calcite crystal in a quartz geode. This is an example of a lucky break when opening the geode, collected in November 1984 on the north side of the Harrodsburg, IN, exit.

A calcite geode in Salem Limestone, from the dump of the Hutson Zinc Mine in Livingston Co., KY. Crystals are small and blocky. Compare to the Salem Limestone geodes in Washington Coi., Indiana.

Pink calcite, probably magnesian, from Harrodsburg, Indiana, found in the early 1980s.

Celestine – Strontium Sulfate – SrSO4

A cluster of celestine in blue, gemmy pseudo-octahedral crystals on quartz. Collected in 1991 during construction of the new Hwy 1638 near Fort Knox, KY.

Celestine in a light blue, gemmy pseudo-octahedral crystal. Collected in 1991 during construction of the new Hwy 1638 near Fort Knox, KY.

Dolomite – Calcium Magnesium Carbonate – CaMg(CO3)2

Dolomite, notice on one side the mineral is pink, and on the other it is orange, colored by iron. Harrodsburg, IN. Collected March 1989.

Ferroan dolomite with microscopic pyrite crystals that have colored the quartz, too. From the road cut near Harrodsburg, Indiana.

Fluorite – Calcium Fluoride – CaF2

Fluorite is the brownish block in the lower left, an etched crystal. Also present are spheres of calcite and brown goethite. From the same location as above.

Goethite – Iron Hydroxide – α-FeO(OH)

Gypsum variety Selenite – Calcium Sulfate – CaSO4.nH2O

Manganese Oxides – MnO2 mostly

This is a close-up of manganese dendrites on calcite from a geode at Harrodsburg, Indiana. The mineral species (often ascribed to pyrolusite) is indeterminant. FOV ~1 cm.

Millerite – Nickel Sulfide – NiS

Millerite in a brassy hair-like tuft with chalcedony. Halls Gap, KY. Bob Harman specimen and photo.

Pyrite – Iron Sulfide – FeS2

Pyrite in small crystal clusters. Their shape resembles dolomite aggregates, so they might be pseudomorphs from dolomite that became ankerite or siderite. With yellow barite on quartz, Calcite removed with HCl. Harrodsburg, Indiana. Cm scale on right.

Strontianite – Strontium Carbonate – SrCO3

Strontianite forms dark brown balls in petroleum-stained quartz. The normal color is white.

Close-up of petroleum-stained strontianite. Notice the small crystals are slightly curved. This is distinctive with this mineral. FOV ~6 mm