The evening sky is royal blue, and you are ready for an incredible night of observing. You load the gear into the vehicle and head to your favorite observing site. Tonight, you are going to push your telescope to its limit, seek out new objects, and revisit old friends. And then…

Some nights you are a well-oiled stargazing machine, while on others, let’s just say the oil was left behind or is a bit coagulated. In other words, things don’t go according to plan. For one reason or another, a stellar night suddenly becomes partly cloudy with a chance of showers. What are the problems observers face? How can they be avoided? Let’s look at a few of them.

Problem 1: A critical component was left behind

Stargazing for most of us is rarely as simple as unloading your telescope and – viola! – You are ready to go. Assembling your telescope and having observing aids at your fingertips is easy-peasy. How often have you left a key component behind?

Repetitive experience allows you to maintain a mental checklist. With age, that checklist might start to fail. The solution is relatively simple, but usually easier said than done. Keep everything in one place and/or create a written checklist with your equipment or in the glove compartment with your registration and insurance.

Think about where you store observing materiel. Is the telescope in the garage or the basement? What about your eyepieces, filters, and binoculars? What about the references you use to plan your observing night? In the good old days, references were called books. You’ve heard of them? Are your books in one place? Old-fashioned sky charts are in another location if they don’t fit in the bookcase.

If you are 100 percent computerized with your references, good for you. Is your database accessible and working? Are all your cords and connectors in good working order and together? Astro-imaging is easier and more popular than ever, but for those who prefer a direct photon-optical nerve interface, do you document what you see? Observation forms can be used for sketching or descriptive notes. You can also transcribe them. Does your sketch pencil have a point? Is the eraser starting to leave smudges? Keep your tools in good shape, and they are less likely to fail!

How about your vehicle? Plenty of gas in the tank?

And don’t forget your phone, snacks, and beverages!

Problem 2: Gravity

Gravity holds your telescope firmly on the ground, but if you drop a small screw or eyepiece, it can cause trouble. Your challenge should be seeing a faint galaxy or detail on Mars, not finding a ¼-inch screw in four-inch-high grass! What about finding that black eyepiece or lens cap for your finder scope in the grass in the dark?

How often have you dropped something at the site – whether in the grass or in an inaccessible gap in your vehicle? A bolt, nut, tool, electrical cord, chart, your observing targets – the list is virtually endless.

A simple solution is to buy a tarp! (Preferably one that isn’t black or silver so you can find things with a red light.) It can be as small as 10 by 10 or large enough to accommodate more observers. With a larger tarp, you can set up a table, chair, lounge-recliner to stargaze with binoculars or watch meteors, or – like me – have a tarp beneath the telescope and pickup truck tailgate. None of my observing area directly contacts the ground. Whatever I drop, I can find.

Problem 3. Can’t find your target

Finding celestial objects could be the subject of an entire article. There can be many different reasons an object cannot be found. I will focus on several common reasons.

When I first began observing, I tried looking for the Owl Nebula with a spotting scope… in the suburbs of a decent-size city. Needless to say, my efforts were fruitless. Some references discuss surface brightness and its importance. Nothing beats hands-on (eyes-on) experience. By blending easy and challenging targets into an observing session, you can modify your target list based on what you can see. If bright objects are looking pathetic, you can save the challenges for another night.

With ‘GoTo’ systems, you can find out quickly the quality of the night sky, good, bad, or the usual. With proper alignment or computer input, one makes a selection and the motors whirr and ‘zero-out’ telling you that your target is now in the center of the field. Well, maybe. Are you looking for an object that is too faint?

If you star-hop to find objects, make sure your finder scope has sufficient aperture and magnification to see the stars for ‘hopping.’ I find 8th to 9th magnitude work stars are ideal. Is your finder well-positioned to look through, or do you have to crane your neck? Are the stars sharply focused? A finder scope is more difficult to use if you have to put on and take off eyeglasses each time to see the sky and the view in the finder in focus. Is the finder fogged up?

Problem 4: Moisture

That brings up another problem that affects most observers at one time or another (or for those not in a desert, most of the time) – moisture. Whether the air temperature is above or below freezing doesn’t matter. Observing in wide-open space is a leading cause of moisture problems. (That’s one reason why home observatories are so popular.)

As the temperature drops after sunset, the humidity increases until the dew point is reached. I’m talking observer’s dew point – where things get wet or ice-covered. That will vary from object to object depending on its composition. Metal and glass are affected much quicker than your clothes. (Dew is the arch enemy of paper.)

Things left out in the open will be affected before those in a contained space. For instance, eyepieces will fog or frost-up before the secondary or primary mirror. Mirrors will fog up much quicker in an open frame telescope tube rather than an enclosed one. Lenses will fog up before mirrors. Light-weight truss telescopes are usually enclosed with black cloth to both keep out stray light and reduce the speed that the mirrors will fog up.

Most observers in humid climes use dew caps (included heated models), battery powered ‘hair dryers,’ and other tools to prevent or evaporate moisture. Large telescopes may come with a fan to circulate air around the primary mirror which – closer to the ground – will fog up sooner. Eyepieces can last longer, but keep them covered. A warm pocket works great.

If you are an old-fashioned paper star chart observer like me, keeping them covered while not in use is essential. An old bed sheet works great because moisture won’t bead up and run, like it will on plastic. Cloth will get wet over time, so if you plan to be out for a long night, bring extra covers.

If you occasionally take breaks in a lounge chair or sleeping bag (which tends to make breaks last longer), cover them when not in use, too. Moisture can ruin sketch pages, so keep them covered. It is easier to get a ‘hole in one’ with a sharp pencil and damp paper than in a round of golf.

Problem 5: Observing impaired

A number of years ago, a young amateur astronomer (not the author!) was determined to make some sketches for an article after an evening of beer drinking with some friends. The result became a legend – a sketch of M11 with star trails. Now some might say that attempting to make an accurate sketch of the Wild Duck Cluster requires a good stiff one or it will be more like a wild goose chase. I have never attempted to plot each star in M11 with my telescope because it would set long before the drawing was done. Congratulations to anyone with the stamina to make the effort. I recommend a caffeinated beverage, not alcohol.

The point is siple: intoxication and star gazing don’t mix, whether you are driving to an observing site or carrying your telescope in your back yard, star gazing is best done unimpaired.

![The author with his [then new] telescope.](https://alangoldsteinsuniverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Alan-Goldstein-with-new-telescope-12-31-1999-600.jpg)

The author with his [then new] 13.1-inch telescope.

Problem 6: There is too much to look for and the sky becomes overwhelming

Have you ever gone out to an observing site where the sky is so dark it takes your breath away? Most of us should be so lucky! What should I look at? New objects? Old friends? Decisions, decisions….

This is where an observing plan comes into play. While stargazing can be relaxing or just plain fun, even a simple plan will increase the pleasure without increasing the burden. Make a list. Magazines, websites and a plethora of books can provide you with an endless selection. (Too much of a good thing can be unhelpful without a plan.)

Consider using established target lists (such as the Astronomical League’s Messier and Herschel object lists). You can create lists of targets based on optimal locations in the sky (especially when light pollution is a problem). A few folks like a list of objects in increasing difficulty, so they can start with easy objects while the sky isn’t perfectly dark (or if a moon is in the western sky) and work down as their eyes are fully adapted.

When I attended the Winter Star Party in the Florida Keys, I created a list of objects based on two criteria: objects too far south for my home latitude and winter objects I don’t have time to look for because it’s too darned cold on clear nights. I was able to observe several dozen new objects because they were on a target list. And what’s really nice – I didn’t bring a scope. I observed with others and made suggestions for targets.

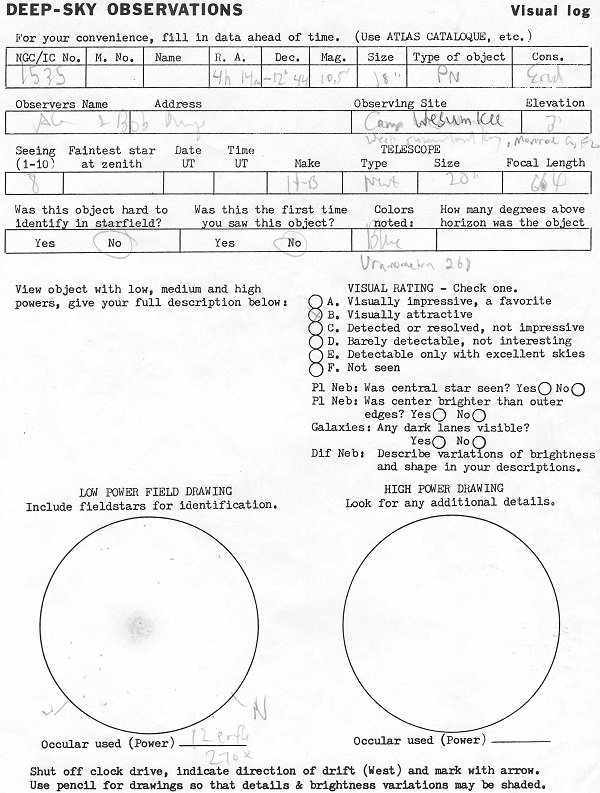

My sketch page for NGC 1535, a winter planetary nebula best sketched under warm Winter Star Party skies, not sub-freezing Kentucky skies!

Except for looking for ‘faint fuzzies’ after observing the moon or a bright planet and ruining your night vision, there is no right or wrong way to plan your observing session. I’ve always had a special place in my heart for galaxies and planetary nebulae, so they are always on my list. After 50+ years as an amateur astronomer, I still love bright Messier objects (especially emission nebulae with their subtle detail), open and globular clusters as well as double stars.

For unfamiliar objects, I’ll go on-line a print out a finder chart. “GoTo’ ay bring the object into the area but not always in the field of view. Many of the computer programs will bring the finder chart into the field. I’ve never been able to adjust between a filtered computer screen and an eyepiece, so printing them out and using a red light is my preference.

These are just a few tips for common observing problems. (Well, maybe not observing impaired…) Think about the worst night of stargazing you had (under a clear sky). What could you have done to prevent what went wrong? Have you done anything to mitigate that disaster? Today is a good day to plan!

The late amateur astronomer, Ben Mayer, at his observatory north of L.A. in 1981. Having an observatory reduces the number of problems compared to a mobile telescope. But mobility has advantages, too.